The Fluoride Lie We've All Been Swallowing

The Fluoride Lie We've All Been Swallowing

I used to brush with fluoride toothpaste twice daily, drink tap water without a second thought, and accept the dentist's fluoride treatments as a normal part of maintaining health. Like most Americans, I never questioned why this chemical was in my water or whether it might be doing more harm than good. That changed when I began researching where fluoride comes from and what it actually does in the human body.

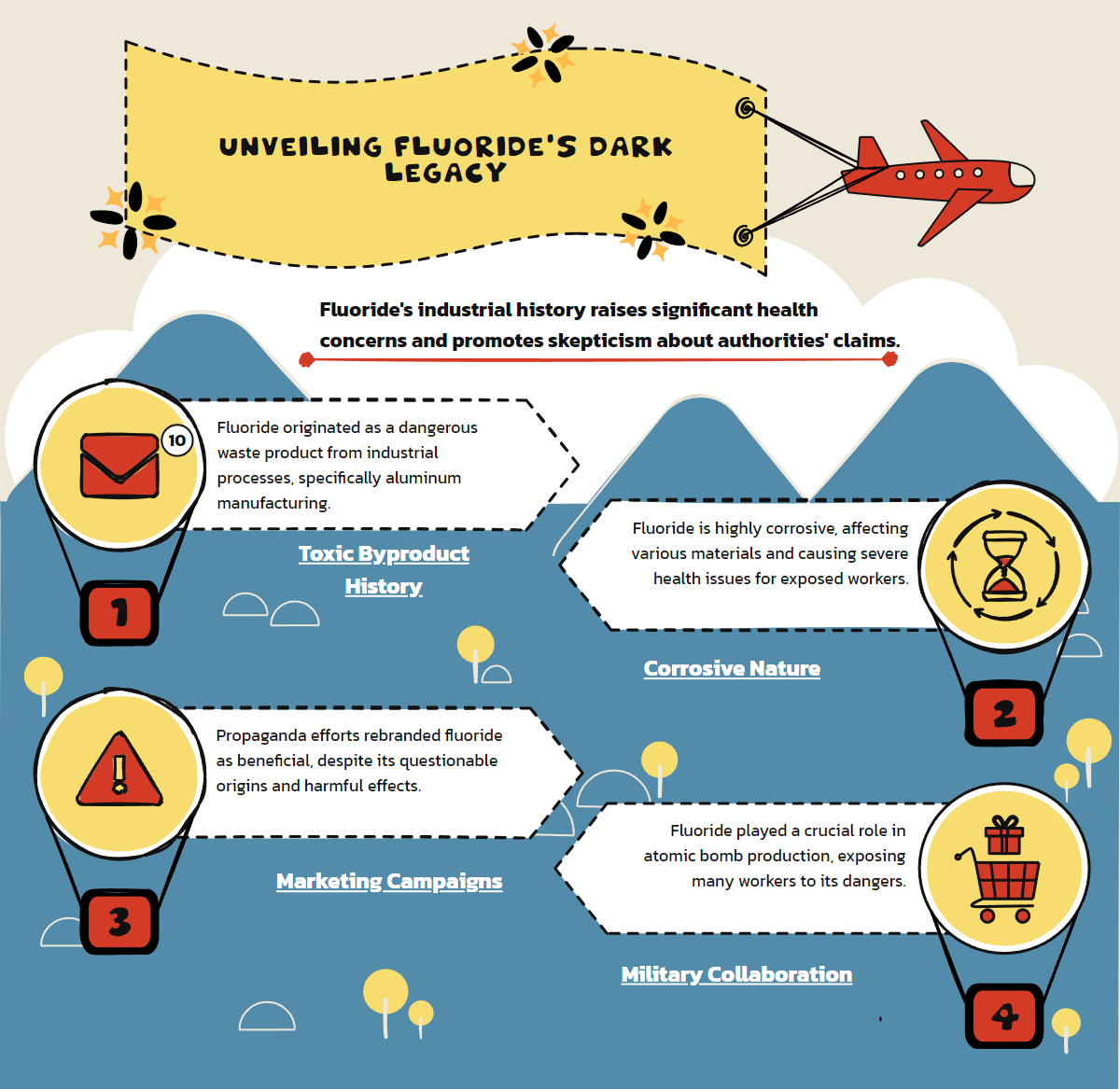

What I discovered shocked me. The substance we've been told protects our teeth began its journey as industrial waste – a troublesome byproduct from aluminum manufacturing and fertilizer production that was expensive to dispose of safely. Rather than paying for proper disposal, industries found a convenient solution: rebrand this waste as a health additive.

This isn't fringe conspiracy theory. It's documented history.

The Industrial Origins We Never Discuss

Fluoride compounds used in water fluoridation are primarily sourced from phosphate fertilizer production. When phosphate rocks are processed with sulfuric acid, they produce two main products: phosphoric acid (used for fertilizers) and hydrogen fluoride and silicon tetrafluoride (toxic byproducts). These fluoride byproducts were once released into the air, damaging nearby crops and livestock until environmental regulations forced industries to capture these emissions.

The problem then became what to do with these captured fluoride compounds. Disposal was expensive. The solution? A remarkable marketing transformation from "industrial waste" to "dental health miracle."

I found it strange that this history is never mentioned by health authorities. They speak of fluoride as if it were developed specifically as a health measure, not an industrial byproduct looking for a home.

Why would they hide this origin story if there was nothing to be concerned about?

The Science They Don't Want You Examining

Proponents point to reduced cavity rates as evidence of fluoride's benefits. What they don't emphasize is that countries without water fluoridation have experienced similar declines in cavity rates. Japan, Belgium, and most of Europe don't fluoridate their water, yet their dental health has improved at rates comparable to fluoridated countries. This suggests other factors like improved nutrition, better oral hygiene practices, and dental care access may be more significant factors in dental health improvements.

Meanwhile, research linking fluoride to health concerns continues to grow. A 2017 study published in Environmental Health Perspectives found that higher fluoride exposure during pregnancy was associated with lower IQ scores in children. A 2018 study in Occupational & Environmental Medicine linked fluoride exposure to reduced thyroid function.

Even the U.S. government has gradually reduced its recommended fluoride levels in drinking water, dropping from 0.7-1.2 mg/L to 0.7 mg/L in 2015. This quiet reduction speaks volumes – if the original levels were truly safe, why reduce them?

I find it deeply troubling that we're only gradually acknowledging these risks after decades of mass exposure.

How Fluoride Actually Works In Your Body

The narrative we've been given is that fluoride primarily works topically, strengthening tooth enamel. But once ingested, fluoride travels throughout your entire body. Unlike nutrients your body needs, fluoride accumulates over time.

Fluoride has a unique attraction to calcium-rich tissues. It concentrates in your bones, where it can alter the crystalline structure, potentially making them more brittle. It accumulates in the pineal gland, which produces melatonin and affects sleep cycles. It crosses the blood-brain barrier. It can disrupt endocrine function, affecting hormones that regulate metabolism, growth and development, tissue function, sexual function, reproduction, sleep, and mood.

I was never told this by any health professional. Were you?

The more I researched, the more I realized how fluoride exemplifies a disturbing pattern in our modern world: the reclassification of industrial chemicals as beneficial substances, supported by limited research often funded by the very industries that benefit from their use.

From Problem to Product: A Case Study in Manipulation

The story of how fluoride transformed from industrial waste to health additive offers a master class in how industrial interests can influence public health policy.

In the 1930s, fluoride emissions were damaging crops and livestock near aluminum plants and phosphate factories. ALCOA (the Aluminum Company of America) faced growing liability from these emissions. The company needed a solution to their fluoride problem.

Enter Andrew Mellon, who served as U.S. Treasury Secretary while being the founder and major stockholder of ALCOA. During his tenure, he appointed dentist H. Trendley Dean to the newly created position at the National Institute of Health to study fluoride effects.

Dean's early research in regions with naturally high fluoride levels suggested a correlation between fluoride and reduced cavities, though these same regions also showed troubling rates of dental fluorosis – a discoloration and mottling of teeth indicating fluoride toxicity.

Despite incomplete research and before long-term safety studies could be conducted, Grand Rapids, Michigan became the first city to artificially fluoridate its water in 1945. The promotion of fluoridation as a public health measure proceeded before the planned 15-year study was even completed.

What troubles me most is how quickly this industrial waste became celebrated as a public health achievement, and how effectively questioning it became associated with fringe thinking rather than legitimate scientific inquiry.

Beyond Fluoride: The Pattern Repeats

Fluoride is just one example of a disturbing pattern. Our food and water supply contains numerous industrial chemicals repurposed as "improvements" to the natural state of our food.

Consider artificial sweeteners – many were discovered during research for other industrial purposes. Aspartame was found during testing of an anti-ulcer drug. Saccharin was discovered by researchers working with coal tar derivatives. Splenda was initially being developed as an insecticide before researchers discovered its sweet taste.

Food preservatives follow similar patterns. BHA and BHT, common food preservatives, are also used in rubber and petroleum products. TBHQ, another preservative, is a form of butane. Sodium nitrite, used in processed meats, becomes potentially carcinogenic nitrosamines in the body.

Even our agricultural practices introduce concerning substances. Glyphosate, the world's most widely used herbicide, is now found in most conventional food products, human blood samples, and even breast milk. It was never intended to enter the human food chain in such quantities.

The commonality? Industrial chemicals finding their way into our bodies, supported by industry-funded research assuring us of their safety, with independent concerns dismissed as unscientific fear-mongering.

Why We Accept What We Should Question

I've often wondered why we so readily accept authorities' assurances about substances like fluoride. I believe several factors contribute to this collective blindspot.

First, there's the powerful appeal to medical authority. When substances are endorsed by dental or medical associations, we assume thorough safety testing has occurred. We don't realize how often these organizations rely on industry-supplied research rather than independent studies.

Second, there's the gradual normalization effect. Most of us grew up with fluoridated water and fluoride toothpaste. Questioning these practices feels like questioning whether we should wash our hands or brush our teeth – it seems absurd to challenge such established norms.

Third, there's confirmation bias. We see that people have fewer cavities than previous generations, so we attribute this to fluoride rather than considering all the other advances in dental care, hygiene practices, and nutrition that have occurred simultaneously.

Finally, there's the unsettling implication of admitting we've been wrong. If fluoride isn't the miracle substance we've been told, what does that say about other chemicals we've accepted into our bodies without question?

Taking Back Control of What Goes Into Your Body

After my research, I made significant changes to reduce my fluoride exposure. I switched to fluoride-free toothpaste and installed a reverse osmosis water filtration system in my home. I'm more conscious about foods that potentially contain high fluoride levels, like conventionally grown produce with fluoride-based pesticide residues, mechanically separated chicken (which can contain bone particles where fluoride concentrates), and certain teas that naturally accumulate fluoride.

I'm not suggesting everyone must eliminate all fluoride exposure. Rather, I believe in the principle of informed consent. We should understand what we're putting into our bodies and have the choice to opt out of chemicals we're concerned about.

The fluoride issue has taught me to question other accepted substances. I now research food additives before consuming them. I look at who funded the safety studies. I ask whether long-term exposure has been adequately studied. I consider whether the substance offers genuine benefits or simply makes processing cheaper for manufacturers.

Most importantly, I've learned that "officially recognized as safe" doesn't always mean what we think it does.

Why This Matters Beyond Personal Health

The fluoride story represents something larger than a single chemical. It exemplifies how industrial interests can reshape public health narratives.

When industrial waste becomes a "nutrient," when questioning established practices becomes "anti-science," when industry-funded research becomes the foundation for public health policy, we should be concerned about more than just our dental health.

These patterns erode public trust in health institutions. When people discover they haven't been given the full story about substances like fluoride, they reasonably begin to question what else they haven't been told.

This distrust doesn't emerge from irrationality – it comes from legitimate pattern recognition. The same institutions repeatedly assure us that various industrial chemicals are perfectly safe, only to later acknowledge concerns after decades of exposure.

We're witnessing this pattern with forever chemicals (PFAS), glyphosate, certain food additives, and various pharmaceutical products that were once declared completely safe before being withdrawn due to health concerns.

A New Approach to Health and Consumption

I'm not advocating for rejection of all modern advances or a return to some idealized past. I'm suggesting a more nuanced, precautionary approach to what we put into our bodies.

Rather than accepting industrial byproducts as health necessities, we might ask whether there are alternatives that don't require introducing novel chemicals into our bodies. For dental health, this might mean focusing more on nutrition, proper oral hygiene, and access to dental care rather than medicating entire water supplies.

Rather than dismissing concerns about industrial chemicals as unscientific, we might recognize that the burden of proof should rest with those introducing these substances, not with the public expected to consume them.

And rather than accepting the narrative that questioning established practices is "anti-science," we might recognize that true science thrives on questioning, skepticism, and continuous reassessment of accepted wisdom.

The fluoride story has taught me that what we swallow – both literally and figuratively – has consequences. I hope more people will research this topic independently, consider the evidence from all sides, and make their own informed decisions about what they're willing to accept into their bodies.

After all, you only get one body. Shouldn't you have the final say in what goes into it?