Our Nutritional Guidelines Might Be Fighting Evolution

Our Nutritional Guidelines Might Be Fighting Evolution

Consider what humans ate for millions of years. Now look at today's food pyramid. The gap between these two realities represents one of the most profound public health experiments ever conducted.

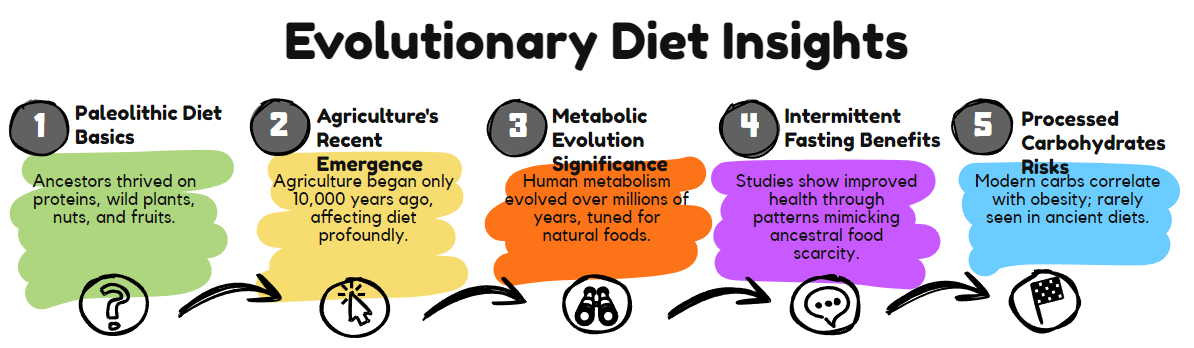

For roughly 2.5 million years, our ancestors thrived as hunter-gatherers. Their diets varied by geography and season but consistently featured animal proteins, wild plants, nuts, and seasonal fruits. Agriculture emerged only 10,000 years ago—a mere blink in our evolutionary timeline. Yet modern nutritional guidelines often treat this recent dietary shift as our natural state.

The Evolutionary Mismatch

Our bodies evolved specific metabolic pathways through countless generations of environmental pressure. These adaptations didn't vanish when we started growing wheat and creating food pyramids. Evolution works slowly, requiring thousands of generations to alter our genetic makeup significantly.

Today's human genome remains roughly 99.9% identical to our Paleolithic ancestors. Our digestive systems, hormonal responses, and metabolic processes were optimized for foods and eating patterns resembling modern dietary recommendations.

When government agencies began issuing nutritional guidelines in the mid-20th century, they prioritized contemporary agricultural outputs and economic factors over evolutionary biology. The resulting recommendations emphasized grains, reduced saturated fats, and promoted frequent eating patterns with almost no precedent in human evolutionary history.

What Science Shows

Recent research suggests our bodies function optimally under conditions that more closely mimic our evolutionary past. Studies on intermittent fasting reveal benefits ranging from improved insulin sensitivity to enhanced cellular repair mechanisms. These findings make perfect sense when considering that our ancestors experienced natural food abundance and scarcity periods.

Similarly, research on carbohydrates' metabolic impacts continues to challenge conventional wisdom. The dramatic increase in diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome correlates strongly with dietary shifts toward processed carbohydrates—foods that would have been virtually nonexistent throughout human evolution.

Protein requirements represent another area where guidelines may miss evolutionary context. Modern recommendations typically suggest modest protein intake, yet archaeological evidence indicates our ancestors often prioritized nutrient-dense animal foods when available. The human brain's extraordinary growth coincided with increased consumption of energy-dense animal products.

Beyond Macronutrients

The evolutionary mismatch extends beyond just what we eat to how we eat. Modern humans consume three meals plus snacks daily, maintaining constant insulin elevation. Contrast this with our ancestors, who experienced natural fasting periods and cyclical food availability.

Food processing represents another critical divergence. Traditional food preparation methods like fermentation, soaking, and slow cooking developed over millennia to enhance nutrient availability and reduce anti-nutrients. Modern ultra-processed foods bypass these protective practices, delivering unprecedented combinations of refined carbohydrates, industrial seed oils, and artificial additives.

Even our eating environment has changed dramatically. Humans evolved consuming foods in natural settings, often after physical exertion, and within social groups. Today, many eat alone, are sedentary, bathe in artificial light, and multitask—conditions that disrupt our innate hunger and satiety signals.

Institutional Resistance to Change

Despite mounting evidence, nutritional guidelines change slowly. Institutional inertia, commercial interests, and the complexity of nutrition science all contribute to this resistance. Guidelines must serve diverse populations and balance multiple health considerations, making dramatic revisions politically challenging.

The original USDA food pyramid, introduced in 1992, recommended 6-11 servings of grains daily while limiting fats of all types. This advice persisted for decades despite rising obesity rates and metabolic disease. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans finally removed the upper limit on total fat consumption, acknowledging that the type of fat matters more than the amount—a shift that took nearly 40 years of research.

Finding an Evolutionary Alignment

Reconciling modern nutritional science with evolutionary biology doesn't require returning to caves or abandoning agriculture. Instead, it means recognizing that our bodies evolved under specific conditions and function best when they are at least partially respected.

This perspective suggests several principles worth considering. First, whole foods generally trump processed alternatives. Second, metabolic flexibility matters—our bodies evolved to handle periods of abundance and scarcity. Third, individual variation exists—different ancestral populations adapted to different food environments.

Most importantly, this evolutionary lens provides context for interpreting nutrition research. When studies show benefits from intermittent fasting, protein-adequate diets, or whole foods, these findings align with our evolutionary heritage. When guidelines promote constant eating, ultra-processed foods, or macronutrient ratios with no evolutionary precedent, skepticism may be warranted.

The Path Forward

Nutritional science stands at a crossroads. Issuing guidelines without evolutionary context risks perpetuating patterns that fight against our biology. Incorporating evolutionary perspectives offers a framework for making sense of conflicting research and developing recommendations that work with, rather than against, our genetic inheritance.

The question isn't whether we should eat exactly like our Paleolithic ancestors—that's neither possible nor necessary. The question is whether our nutritional guidelines should acknowledge the evolutionary forces that shaped human metabolism. Our bodies represent the culmination of millions of years of adaptation. Perhaps our dietary recommendations should finally catch up.