Your Body Remembers Being an Apex Predator

Your Body Remembers Being an Apex Predator

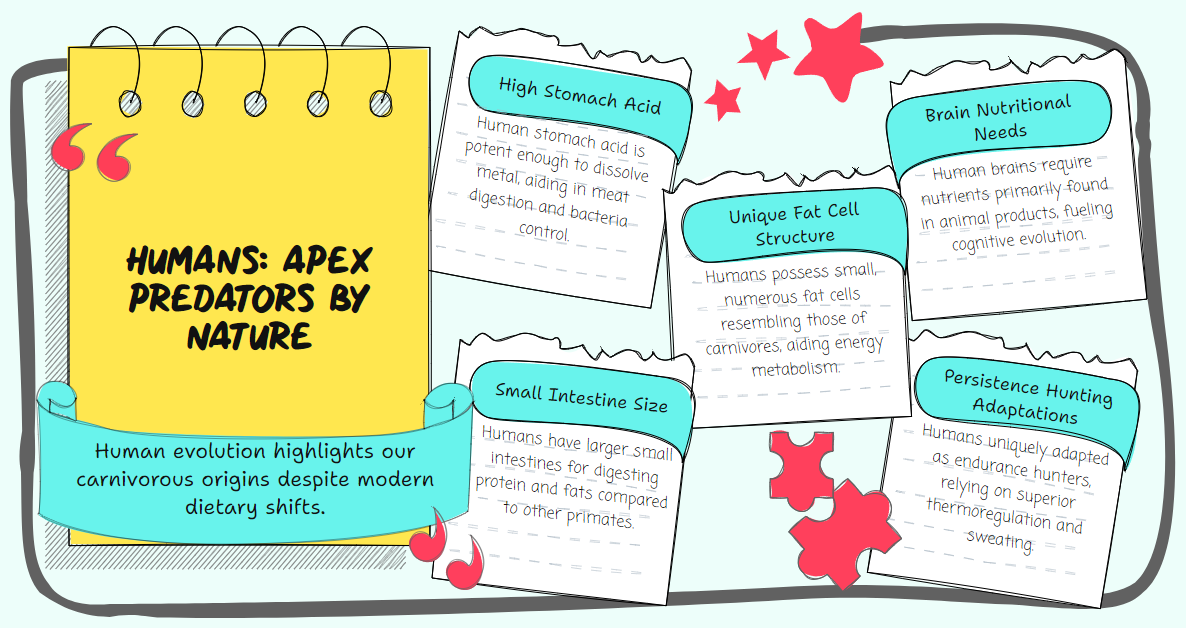

The human stomach contains acid powerful enough to dissolve metal. This isn't a random quirk of biology. It's a deliberate adaptation with a specific purpose: to kill dangerous bacteria in raw meat.

While modern humans consume plants and grains in abundance, our bodies tell a different evolutionary story. The evidence is written in our physiology, metabolism, and genes—a biological memory spanning two million years.

What if much of what we assume about human dietary evolution is incomplete?

The Two-Million-Year Hunt

Humans were apex predators for approximately two million years, according to research by Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Prof. Ran Barkai of Tel Aviv University. Only after the extinction of larger animals (megafauna) did humans gradually increase plant consumption in their diet.

Our genus's position in the food web became highly carnivorous around 2.5 million years ago and remained that way until the upper Paleolithic, roughly 11,700 years ago. This timeline contradicts popular narratives that frame humans as primarily plant-eaters who occasionally consume meat.

The shift toward our current more plant-based diet began relatively recently, only about 85,000 years ago, possibly triggered by declining animal food sources. This represents just a brief moment in our evolutionary history.

"Human behavior changes rapidly, but evolution is slow. The body remembers," explains Dr. Ben-Dor.

Your Inner Carnivore

The evidence for our predatory past isn't found in speculation but in the concrete architecture of our bodies.

Consider our stomach acidity. Humans maintain an extremely high stomach acidity (pH 1.5), placing us firmly in the carnivore/scavenger range. This is not a coincidental feature but an expensive evolutionary adaptation that requires significant physiological machinery to produce and contain this corrosive material.

Evolution doesn't waste resources. Such adaptations only persist under substantial selective pressure.

Our fat cell structure further betrays our predatory heritage. Unlike herbivores and omnivores, whose fat cells are few but large, humans have small and numerous fat cells—a pattern matching other carnivorous species. This structure supports an energy metabolism adapted to deriving most energy from lipids and proteins rather than carbohydrates.

Even our intestines tell the carnivore story. Our small intestine is approximately 60% larger than our primate cousins, specialized for digesting protein and fats. Meanwhile, our large intestine, where plant fiber fermentation occurs, is relatively smaller.

The result? Primates have protruding bellies while humans (at least non-obese ones) have flat abdomens—a critical advantage for a hunting species. You don't see bulging bellies on wolves or tigers.

The Brain That Meat Built

The human brain requires substantial energy and specific nutrients to function. The fatty acids that compose 90% of our brains (AA, DTA, DHA, EPA) are predominantly found in animal products, not plants.

This nutritional reality aligns with the Expensive Tissue Hypothesis, which proposes that around 1.5 million years ago, early humans began consuming more meat. This compact, high-energy food source doesn't require an extensive digestive system.

The evolutionary trade-off was elegant: smaller guts for bigger brains. The concentrated nutrition in meat allowed our ancestors to fuel growing neural complexity while reducing metabolically expensive intestinal tissue.

This dietary shift coincided with dramatic increases in brain size, suggesting that animal-derived nutrients were essential catalysts for our cognitive evolution.

Built to Hunt

Perhaps our unique hunting adaptations are the most remarkable evidence of our predatory past. Humans evolved as persistent hunters—predators who could pursue prey to exhaustion through superior endurance.

This hunting strategy is enabled by several distinctive human traits: profuse sweating, minimal body hair, arched feet, and long Achilles tendons. We are the only ape that effectively dissipates heat through sweating while maintaining elevated activity.

Our thermoregulation system provides a subtle but critical advantage that our intelligence magnifies to achieve the seemingly impossible: running down faster quarry.

Unlike predators targeting the weak, old, or young, early humans uniquely hunted prime adult animals. Archaeological evidence from countless sites demonstrates humans' expertise as hunters of large animals, so effective that human hunting likely played a significant role in megafauna extinction.

We are the only primates to consume animals larger than ourselves regularly.

The Reluctant Omnivore

If humans were such effective carnivores, why did we eventually shift toward more plant consumption?

The archaeological record suggests necessity, not preference, drove this change. As large animal populations declined worldwide, humans who could derive more nutrition from plants gained a survival advantage.

This transition wasn't immediate or universal. Tools associated with processing plants only appeared around 40,000 years ago and increased frequently around the agricultural revolution.

The evidence suggests humans remained carnivorous as long as possible, only diversifying their diet when ecological pressures demanded it.

Remembering Our Predatory Past

This evolutionary history isn't merely academic. It provides context for understanding today's human physiology, metabolism, and nutritional needs.

Our bodies still carry the metabolic machinery optimized for a diet rich in animal proteins and fats. The rapid transition to grain-based diets that occurred with agriculture represents a dramatic departure from the nutritional environment that shaped us for millions of years.

This doesn't mean modern humans must eat like Paleolithic hunters. Evolution has granted us remarkable adaptability. However, it does suggest that our understanding of optimal human nutrition should acknowledge our lengthy carnivorous heritage.

The body remembers what the mind forgets. For two million years, it remembered being an apex predator.