The Vegetarian Myth That Blinds Environmental Progress

The Vegetarian Myth That Blinds Environmental Progress

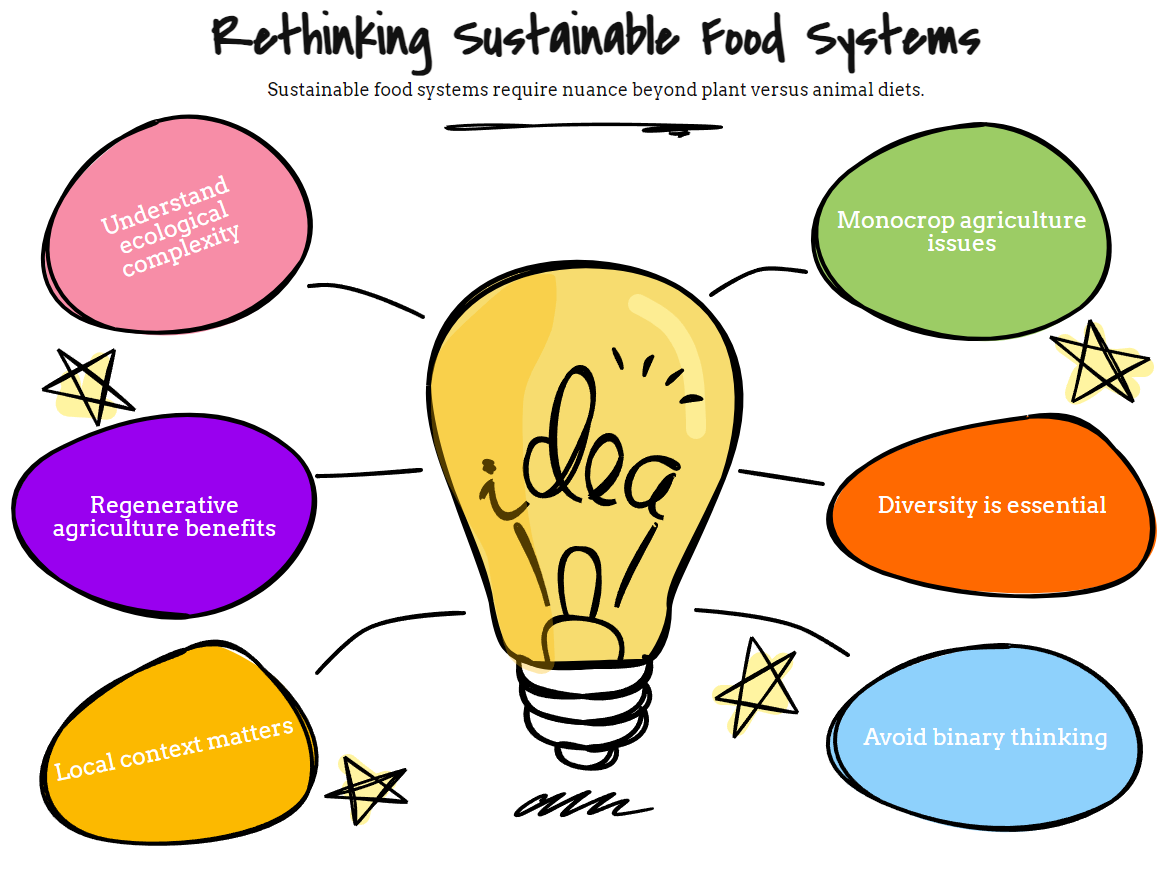

Simple truths comfort us. They offer clean narratives in a messy world. Perhaps no environmental "truth" has gained more widespread acceptance than the idea that plant-based diets represent our ecological salvation. But what if this narrative, despite its good intentions, blinds us to the complexity of truly sustainable food systems?

Our cultural conversation about food sustainability often follows a predictable script: animal agriculture destroys ecosystems, plant agriculture saves them. This binary framing makes for compelling messaging but obscures the nuanced reality of how human food systems interact with natural environments.

When Plant-Based Solutions Create New Problems

The environmental case for vegetarianism typically rests on three pillars: reduced greenhouse gas emissions, decreased land use, and lower water consumption. These arguments contain legitimate concerns about industrial animal agriculture. Yet they often fail to acknowledge that large-scale plant agriculture brings its ecological challenges.

Consider modern monocrop agriculture. Vast fields of single crops require intensive tillage that disrupts soil ecosystems and releases carbon. They demand petroleum-based fertilizers, synthetic pesticides, and irrigation systems that deplete aquifers. The annual plowing of millions of acres has contributed to the loss of nearly half the world's topsoil in recent decades.

This isn't to suggest that plant agriculture is inherently problematic. The issue lies in how we practice it. The same criticism applies to animal agriculture. The problem isn't simply animals versus plants but rather industrial versus regenerative approaches to food production.

The Missing Context of Ecosystem Function

Properly managed livestock can restore degraded landscapes. Grazing animals, when moved frequently in patterns that mimic natural herbivore behavior, stimulate plant growth, increase soil organic matter, and enhance biodiversity. These systems sequester carbon while producing nutrient-dense food from land unsuitable for crop production.

Many grassland ecosystems co-evolved with grazing animals. Removing these animals doesn't restore these landscapes to some pristine state but instead disrupts established ecological relationships. Appropriate grazing maintains ecosystem health in regions like the American Great Plains or African savannas.

The vegetarian environmental narrative often overlooks these ecological relationships, presenting a simplified version of sustainability that doesn't account for regional differences or ecosystem complexity.

The Global Nutrition Question

Food systems must sustain landscapes and nourish humans. Again, the conversation requires nuance. Plant-based diets can provide adequate nutrition, but they may not represent the optimal approach for all populations.

In regions with limited arable land but abundant grasslands, animal products often provide essential nutrients that would otherwise be unavailable or require environmentally costly importation. Local animal products may represent the most sustainable nutrition source for populations in harsh northern climates or arid regions.

The question isn't whether humans can survive on plants alone—many clearly can—but whether universal vegetarianism represents the most environmentally sound approach to feeding humanity while regenerating ecosystems.

Beyond Binary Thinking

The path forward requires moving beyond the plant versus animal binary. Truly sustainable food systems integrate both plants and animals in ways that mimic natural ecosystems rather than fighting against them.

This might look like diverse polycultures where livestock rotate through crop fields, fertilize the soil, and control pests. It might also resemble silvopasture systems, where animals graze among trees that sequester carbon and provide habitat. It might also look like integrated rice and duck farming, where birds control weeds and insects while fertilizing crops.

These integrated approaches often outperform both conventional animal agriculture and monocrop plant production regarding total ecosystem health, resilience, and productivity per acre.

Toward True Food Sustainability

None of this negates the legitimate concerns about industrial animal agriculture. Factory farming systems that concentrate animals, pollute watersheds, and require massive grain inputs deserve criticism. But the solution isn't necessarily eliminating animal products.

Instead, we might focus on how animals are integrated into agricultural systems. The distinction between extractive and regenerative practices matters more than the simplistic plant versus animal dichotomy.

Environmental vegetarianism often springs from genuine concern for planetary health, and those concerns remain valid. However, addressing our ecological crisis requires moving beyond comfortable myths toward a more nuanced understanding of how human food systems can work with rather than against natural processes.

The most sustainable diet might not be universally plant-based or meat-centered but rather regionally appropriate, ecologically sound, and integrated with local ecosystems. This approach lacks the simplicity of "go vegan to save the planet" messaging but offers something more valuable: a path toward truly regenerative food systems that can nourish both people and planet for generations to come.

Perhaps the most dangerous myth isn't about vegetarianism but rather our persistent belief that complex ecological challenges have simple, universal solutions. Like the ecosystems they depend upon, our food systems thrive on diversity rather than dogma.