The Silent Killer In Your Kitchen

The Silent Killer In Your Kitchen

We fear cigarettes but celebrate birthday cake.

This contradiction reveals something profound about our relationship with risk. While we've successfully vilified smoking through decades of public health campaigns, we've simultaneously normalized a threat that claims even more lives.

Junk food kills more people than smoking.

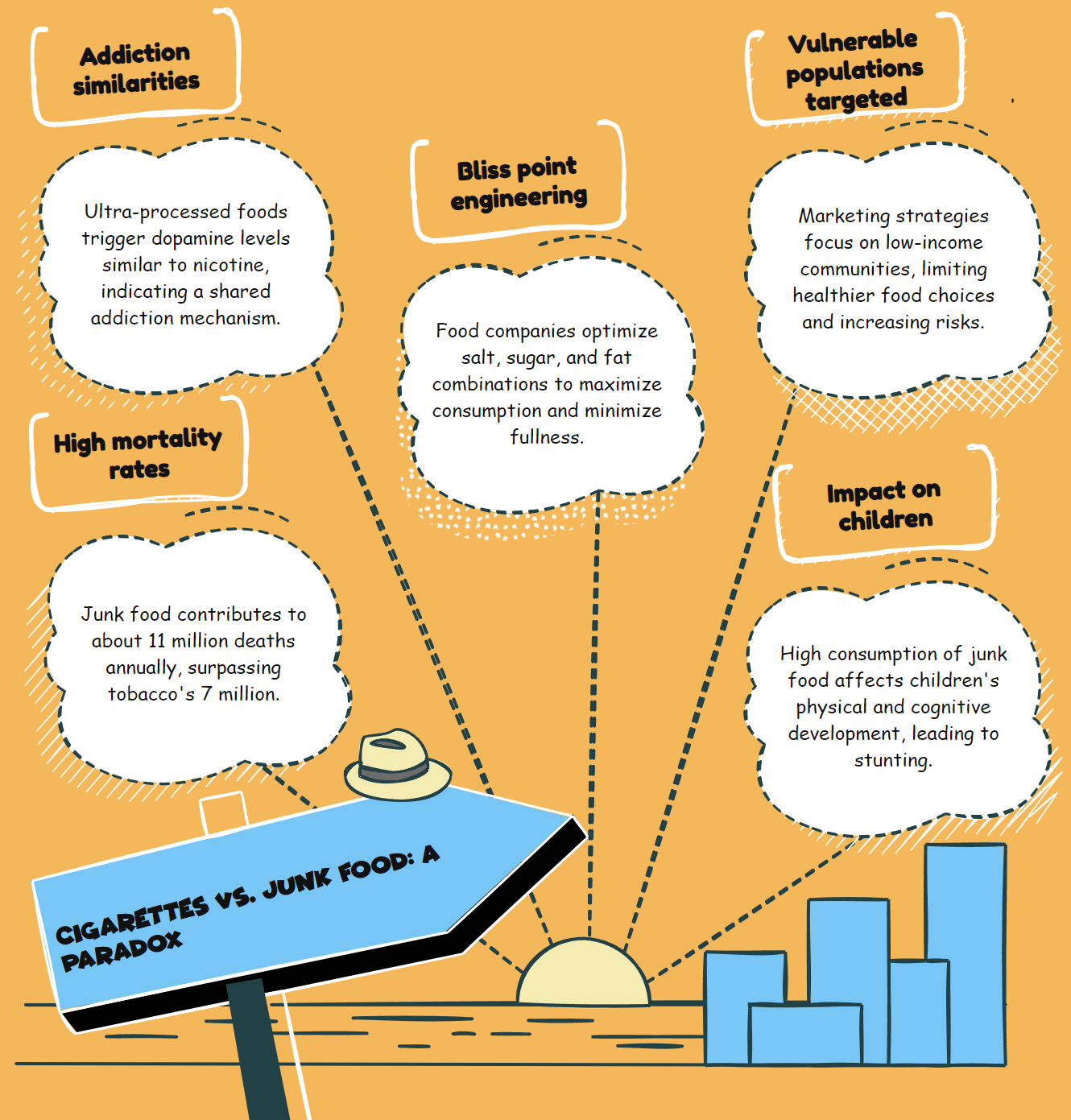

According to the World Health Organization, ultra-processed foods are responsible for approximately 11 million deaths annually, while tobacco claims around 7 million lives each year. This isn't a marginal difference—it's a public health catastrophe hiding in plain sight.

The comparison between cigarettes and junk food runs deeper than mortality statistics.

The Addiction Parallel

We understand that nicotine is addictive. We accept that tobacco companies engineered cigarettes to maximize this addiction. Yet we've been slower to recognize that ultra-processed foods follow the same playbook.

Scientific research has shown that refined carbohydrates and fats in ultra-processed foods trigger similar levels of dopamine in the brain as nicotine and alcohol. This isn't coincidental—it's by design.

Food manufacturers have systematically engineered products to hit what industry insiders call "the bliss point"—the perfect combination of salt, sugar, and fat that maximizes consumption while minimizing satiety.

The speed of delivery matters too. Just as a cigarette delivers nicotine to the brain more rapidly than a patch, ultra-processed foods deliver carbohydrates and fats to the gut faster than whole foods. This rapid delivery increases their addictive potential.

The result? A systematic analysis of 281 studies from 36 countries found that food addiction affects 14% of adults and 12% of children. These numbers mirror addiction rates for many controlled substances.

Beyond Personal Choice

Both the tobacco and food industries have relied heavily on the narrative of personal responsibility.

"It's your choice to smoke," they said.

"It's your choice what you eat," they say now.

This framing conveniently ignores how these industries have shaped our environment, options, and brain chemistry. It disregards how poverty restricts food choices and how marketing targets vulnerable populations.

Research from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington has found that "poor diet is the leading risk factor for deaths in the majority of the countries of the world." Their study concluded that unhealthy diets are "a larger determinant of ill health than either tobacco or high blood pressure."

The consequences extend far beyond obesity.

A Pandemic of Diet-Related Disease

Ultra-processed foods have been linked to more than 200 medical conditions. The list includes various cancers, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and dementia.

Perhaps most alarming is the impact on children. In countries with high consumption of ultra-processed foods, children are physically shorter by measurable amounts—a form of nutritional stunting previously associated only with severe poverty.

This stunting isn't just physical. Cognitive development is intimately connected to nutrition. A generation raised on ultra-processed foods may face intellectual limitations that we're only beginning to understand.

While cigarettes kill their users, junk food threatens entire populations across generations.

The Industry Connection

The parallels between big tobacco and big food aren't coincidental. Several major food brands were once owned by the world's largest tobacco companies.

The tactics used to formulate and market cigarettes were applied directly to food products. The science of addiction was transferred from one industry to another.

Both industries have fought regulation through similar strategies. Both have funded research designed to create doubt about health impacts. Both have targeted children and vulnerable populations with their marketing.

Both have positioned themselves as champions of freedom and personal choice while engineering products designed to override our ability to choose freely.

A Different Approach

The solution isn't as simple as demonizing certain foods or food companies. Unlike tobacco, we can't advocate for complete abstention from food.

Instead, we need a fundamental shift in how we think about our food system.

First, we must recognize that the problem isn't processed food in general. Traditional processing methods like fermenting, curing, and preserving have been part of human food cultures for millennia and often enhance nutritional value.

The issue is specifically with ultra-processed foods—products engineered from industrial ingredients and additives rather than whole foods.

Second, we need to acknowledge that individual willpower is an insufficient solution. The science is precise that these products are designed to override our natural satiety mechanisms.

Just as we addressed smoking through systemic changes—warning labels, advertising restrictions, public space bans, and taxes—we need structural approaches to our food environment.

This includes regulating marketing to children, ensuring access to affordable whole foods in all communities, and requiring transparent labeling that reflects actual health impacts rather than industry-friendly metrics.

The Path Forward

The good news is that we've successfully changed our relationship with tobacco. Smoking rates have declined dramatically in most developed countries, and we've created a template for addressing harmful industries.

The challenge with food is greater. Food is necessary for life. Food is cultural. Food is pleasure, connection, and tradition.

Yet we've allowed a small group of corporations to transform our food system from one based on nourishment to one based on profit maximization through addiction.

The most powerful step we can take is to reclaim our understanding of what food is. Food is not just calories or macronutrients; it is not just fuel.

Real food nourishes not just our bodies but also our communities and our planet. It connects us to cultural traditions and agricultural practices developed over thousands of years.

We see our choices differently by recognizing ultra-processed products not as food but as industrial commodities designed for profit rather than nourishment.

This shift in perspective doesn't require perfect eating or moral purity. It simply means approaching our food system with the same critical awareness we now bring to cigarettes.

The cigarette was once ubiquitous, normalized, and celebrated. Today, we understand it as a deadly, addictive product engineered for profit at the expense of human health.

The ultra-processed food products that dominate our food system deserve the same recognition.

Our kitchens shouldn't contain more dangers than a tobacco shop.