The Great Fat Deception: Rethinking Heart Disease Causes

The Great Fat Deception: Rethinking Heart Disease Causes

For decades, we've been told a simple story about heart disease. Eat saturated fat, raise your cholesterol, clog your arteries, and have a heart attack. For generations, this narrative has shaped dietary guidelines, pharmaceutical interventions, and public health policy.

But what if this story is fundamentally flawed?

The saturated fat and cholesterol theory of heart disease is one of the past century's most influential medical paradigms. Yet growing evidence suggests it may also be one of medicine's most significant scientific missteps.

The Birth of a Theory

The story begins in the 1950s when heart disease had rapidly become America's leading killer. Scientists scrambled to identify the cause of this apparent epidemic.

Enter Ancel Keys, a physiologist who would forever change how we think about food and health. Keys developed the "diet-heart hypothesis," proposing that dietary saturated fat raises blood cholesterol, which accumulates in arteries and causes heart attacks.

His famous Seven Countries Study showed a clear connection between countries with high saturated fat consumption and high rates of heart disease. This research became the foundation for decades of public health recommendations.

But there was a problem.

Keys had data from 22 countries but only included seven in his final analysis. The countries he cherry-picked happened to support his hypothesis, while those that contradicted it—like France and Switzerland with high fat consumption but low heart disease rates—were excluded.

Despite these methodological flaws, the hypothesis gained momentum. By the 1970s, the American Heart Association and the U.S. government were recommending low-fat diets to prevent heart disease.

The war against fat had begun.

The Cholesterol Confusion

As the saturated fat theory took hold, cholesterol—particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL)—was branded the villain in the heart disease story.

The logic seemed straightforward: LDL carries cholesterol in the bloodstream, which builds up in arteries. Therefore, lowering LDL reduces the risk of heart disease.

This reasoning led to the development and widespread prescription of statins, drugs designed to lower LDL cholesterol. Today, these medications are among the most prescribed in the world.

But the relationship between cholesterol and health is far more complex than initially believed.

Cholesterol is not simply a harmful substance to be minimized. It's a vital molecule that forms the structural integrity of every cell in your body. It's essential for hormone production, vitamin D synthesis, and proper brain function.

More surprising is the growing evidence that higher LDL levels may be protective in older adults. A review of 19 studies with over 68,000 elderly participants found that higher LDL cholesterol was associated with greater longevity, not increased mortality.

This paradoxical finding challenges the very foundation of our approach to heart disease prevention.

When Evidence Contradicts Theory

If saturated fat and high cholesterol truly caused heart disease, specific patterns should be consistently observable in populations worldwide. Yet numerous contradictions exist.

The French Paradox is perhaps the most famous challenge to the diet-heart hypothesis. Despite consuming diets rich in saturated fats from cheese, butter, and meat, the French have significantly lower rates of heart disease than would be predicted by the traditional theory.

While some attribute this to wine consumption or lifestyle factors, these explanations fail to resolve the fundamental contradiction: high saturated fat intake does not reliably predict heart disease rates across populations.

Other inconsistencies abound. Multiple large-scale studies have failed to find a consistent link between saturated fat consumption and heart disease. The Women's Health Initiative, one of the most extensive nutrition studies ever conducted, found no reduced heart disease risk among women following low-fat diets.

Perhaps most telling is that despite decades of low-fat dietary advice and widespread statin use, heart disease remains the leading cause of death in developed nations.

If our theory were correct, shouldn't our interventions be more effective?

Beyond LDL: A More Nuanced View

Modern research reveals that cardiovascular disease is far more complex than the simple "cholesterol clogs arteries" model suggests.

We now understand that the amount of LDL matters, as does the size, number, and condition of LDL particles. Small, dense LDL particles can more easily penetrate artery walls and become oxidized, while larger, "fluffier" particles appear less harmful.

Inflammation and oxidative stress play crucial roles in arterial damage. Without these factors, cholesterol doesn't simply "stick" to healthy arteries.

The triglyceride-to-HDL ratio has emerged as a much stronger predictor of heart disease risk than LDL alone. This ratio serves as a proxy measure for insulin resistance and metabolic health, factors increasingly recognized as fundamental to cardiovascular disease development.

Blood sugar regulation, endothelial function (the health of the artery lining), and clotting factors contribute significantly to heart disease risk, often independently of cholesterol levels.

Why Did We Get It So Wrong?

How did such a flawed theory become deeply entrenched in medical practice and public consciousness?

Several factors contributed to this scientific inertia.

First, the simplicity of the cholesterol hypothesis made it easy to communicate and implement. "Fat clogs arteries" creates an intuitive mental image that's far easier to grasp than the complex interplay of inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and vascular biology.

Second, powerful economic interests became invested in the theory. The food industry profited enormously from new low-fat, high-carbohydrate products, and pharmaceutical companies built billion-dollar businesses around cholesterol-lowering medications.

Third, institutional momentum made challenging the status quo professionally risky. Scientists who questioned the lipid hypothesis often found themselves marginalized, their research funding threatened, and their work subjected to unusual scrutiny.

The result was decades of nutritional advice that may have inadvertently worsened the problems it aimed to solve.

The Real Drivers of Heart Disease

What is if saturated fat and LDL cholesterol aren't the primary culprits in heart disease?

A growing consensus points to several interconnected factors:

Chronic inflammation damages arterial walls and promotes plaque formation. Sources of inflammation include processed foods, environmental toxins, chronic infections, and psychological stress.

Metabolic dysfunction, particularly insulin resistance, disrupts normal energy metabolism and promotes inflammation. The primary drivers are excessive consumption of refined carbohydrates and industrial seed oils and insufficient physical activity.

Endothelial damage to the delicate lining of blood vessels creates the conditions for atherosclerotic plaque development. Smoking, high blood pressure, and glycation from elevated blood sugar all contribute to this damage.

Oxidative stress damages LDL particles and cellular structures. Without oxidation, LDL particles don't readily participate in plaque formation, regardless of their concentration in the bloodstream.

These factors work synergistically, creating a perfect storm for cardiovascular disease development.

Rethinking Prevention

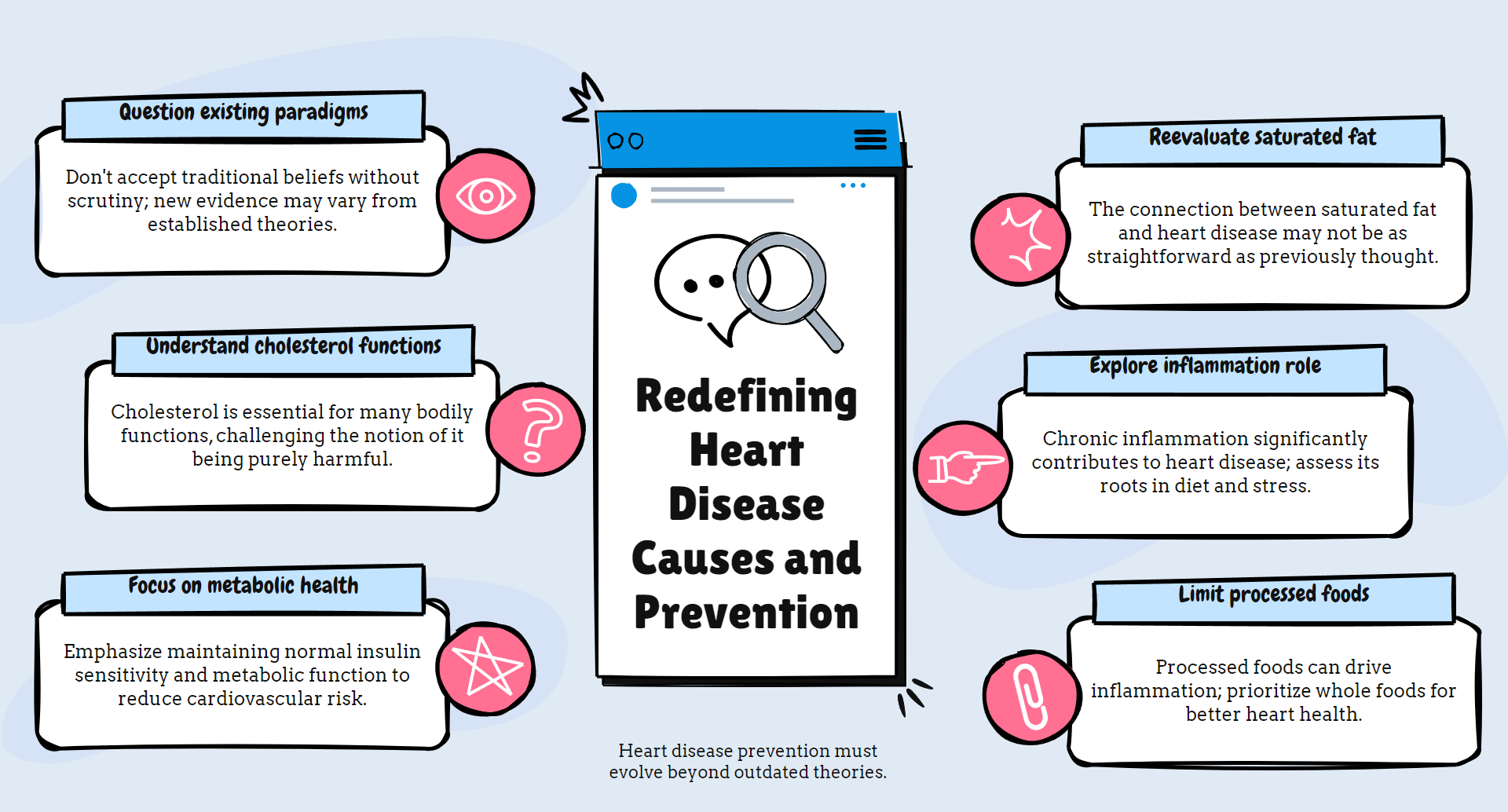

If our understanding of heart disease is changing, our approach to prevention must evolve as well.

Rather than focusing narrowly on LDL cholesterol and saturated fat restriction, a more effective strategy addresses the root causes of vascular damage and inflammation:

Prioritize whole, unprocessed foods that support metabolic health. This includes nutrient-dense animal proteins, vegetables, fruits, and natural fats.

Minimize refined carbohydrates and industrial seed oils that promote inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

Manage blood glucose and insulin levels through appropriate carbohydrate intake, meal timing, and physical activity.

Address lifestyle factors, including stress management, quality sleep, and regular movement.

Look beyond standard lipid panels to more meaningful cardiovascular risk markers, such as triglyceride-to-HDL ratio, hsCRP (inflammation), HbA1c (blood sugar control), and advanced imaging when appropriate.

The Path Forward

Scientific progress requires the willingness to question established beliefs when evidence contradicts them. The saturated fat and cholesterol theory of heart disease represents a paradigm in desperate need of revision.

This isn't about assigning blame for past mistakes. It's about acknowledging new evidence and adapting our approach accordingly.

This evolving understanding offers both challenge and opportunity for individuals concerned about heart health. It means questioning conventional wisdom and perhaps changing deeply ingrained habits. But it also offers new pathways to cardiovascular health that don't require fear of traditional foods or lifelong medication.

For medical professionals and researchers, it means remaining open to evidence contradicting established theories, however uncomfortable that may be.

The story of heart disease is being rewritten. The new narrative is more complex than the old one, but it's also more hopeful—and likely more accurate.

Our understanding continues to evolve. But one thing seems increasingly clear: the simple story we've been told about saturated fat, cholesterol, and heart disease is due for a significant revision.