The Forgotten Carnivore Within Us

The Forgotten Carnivore Within Us

Teeth tear flesh. Blood nourishes the brain. Evolution shapes bodies.

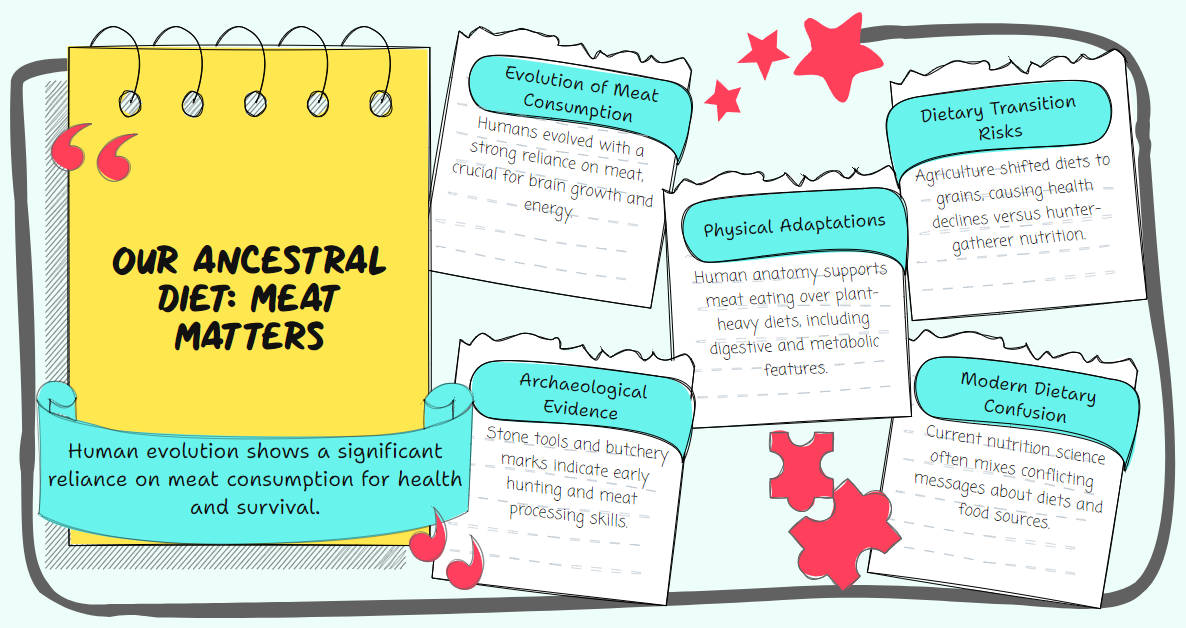

For millions of years, our ancestors hunted and consumed animals, gradually adapting their bodies to extract maximum nutrition from meat. Yet today, we debate whether humans should eat meat at all. This tension between our evolutionary heritage and modern dietary choices raises profound questions about our nature and optimal health.

The story of human diet is written in our bones, genes, and guts. It's a narrative that spans millions of years, with meat playing a starring role that many modern conversations overlook or minimize. Understanding this carnivorous heritage provides crucial context for today's nutritional debates.

Our Ancestral Dinner Table

The archaeological record tells a compelling story. Around 2.6 million years ago, our early hominin ancestors began using stone tools to process animal carcasses. Isotope analyses of fossil remains reveal that early humans consumed significant quantities of animal protein. Butchery marks on ancient bones show deliberate, skilled meat processing techniques that evolved over hundreds of thousands of years.

Perhaps most telling is the dramatic encephalization—brain growth—in the human lineage. Our brains tripled in size throughout evolution, requiring tremendous energy input. Many anthropologists argue that this development would have been impossible without meat's caloric density and nutritional profile.

The evidence suggests our ancestors weren't just occasional meat-eaters but skilled hunters who relied heavily on animal foods. They tracked prey across vast distances, developed sophisticated hunting technologies, and organized complex social structures partly around meat acquisition and sharing.

Written in Our Biology

Our bodies tell the same story as the archaeological record. Unlike obligate herbivores, humans lack specialized digestive features for processing large quantities of plant matter. We have relatively small colons, the gut section responsible for fermenting fibrous plant materials. Our stomach acidity closely resembles that of scavengers and predators, not plant-eaters.

Our nutritional requirements further reveal our carnivorous adaptations. Humans must be prepared with vitamins A, B12, DHA, and other nutrients naturally concentrated in animal foods. While we can convert some plant precursors into these essential nutrients, the conversion rates are often inefficient, suggesting an evolutionary history that included regular animal food consumption.

Even our metabolism shows signs of adaptation to meat consumption. Humans can efficiently process protein and fat for energy, with some indigenous populations historically thriving on diets where these macronutrients provided the vast majority of calories.

The Agricultural Revolution and Beyond

Roughly 10,000 years ago, humans began a massive dietary experiment with the advent of agriculture. This shift toward grain-based diets represented a dramatic departure from the meat-centered eating patterns that had sustained human evolution for millions of years.

The archaeological record shows that this transition came with costs. Early agricultural populations experienced reduced stature, increased infectious disease, dental problems, and nutritional deficiencies compared to their hunter-gatherer predecessors. These findings challenge the narrative that plant-based agriculture represented straightforward progress in human nutrition.

The Industrial Revolution brought another seismic dietary shift. Processed foods, refined carbohydrates, vegetable oils, and sugar became dietary staples—foods that barely existed throughout most of human evolution. This deviation from our ancestral diet pattern coincides with the rise of modern chronic diseases.

Rethinking Modern Nutrition

Today's nutritional landscape is characterized by confusion and contradictory advice. Government guidelines promote grain-heavy diets, while some clinical research suggests benefits from higher protein, lower carbohydrate approaches that more closely resemble ancestral eating patterns.

Interesting clinical findings have emerged from studies of meat-centered diets. Some research indicates potential benefits for weight management, blood sugar control, and even autoimmune conditions when people adopt diets higher in animal proteins and fats. These preliminary results suggest our biology may still be optimized for the types of foods that fueled our evolution.

The conversation around meat also requires environmental nuance. While industrial meat production raises legitimate sustainability concerns, regenerative agriculture models suggest animal husbandry can benefit ecosystems when correctly managed, much as wild herbivores shaped healthy landscapes for millions of years.

Beyond Dietary Dogma

The evidence of our carnivorous heritage doesn't dictate that everyone must eat meat, but it does suggest we should approach nutritional science with evolutionary context. Our bodies evolved specific adaptations to process animal foods efficiently, and these biological realities deserve consideration in dietary recommendations.

Perhaps the most reasonable conclusion is that humans evolved as adaptable omnivores with a strong carnivorous tendency. Our ancestors ate what was available, but animal foods provided crucial nutrients that fueled our distinctive development as a species.

This evolutionary perspective invites us to question simplistic dietary narratives and consider more nuanced approaches to nutrition. Understanding where we came from gives us valuable insights into what might truly nourish us today. The story written in our biology and evolutionary history deserves a voice in our ongoing conversation about optimal human nutrition.

The forgotten carnivore within us still shapes our nutritional needs, whether or not we choose to acknowledge it. As we navigate complex dietary choices in the modern world, this ancestral wisdom offers a valuable compass that might guide us toward better health.