Ruminants Transform What Humans Cannot Eat Into Perfect Nutrition

Ruminants Transform What Humans Cannot Eat Into Perfect Nutrition

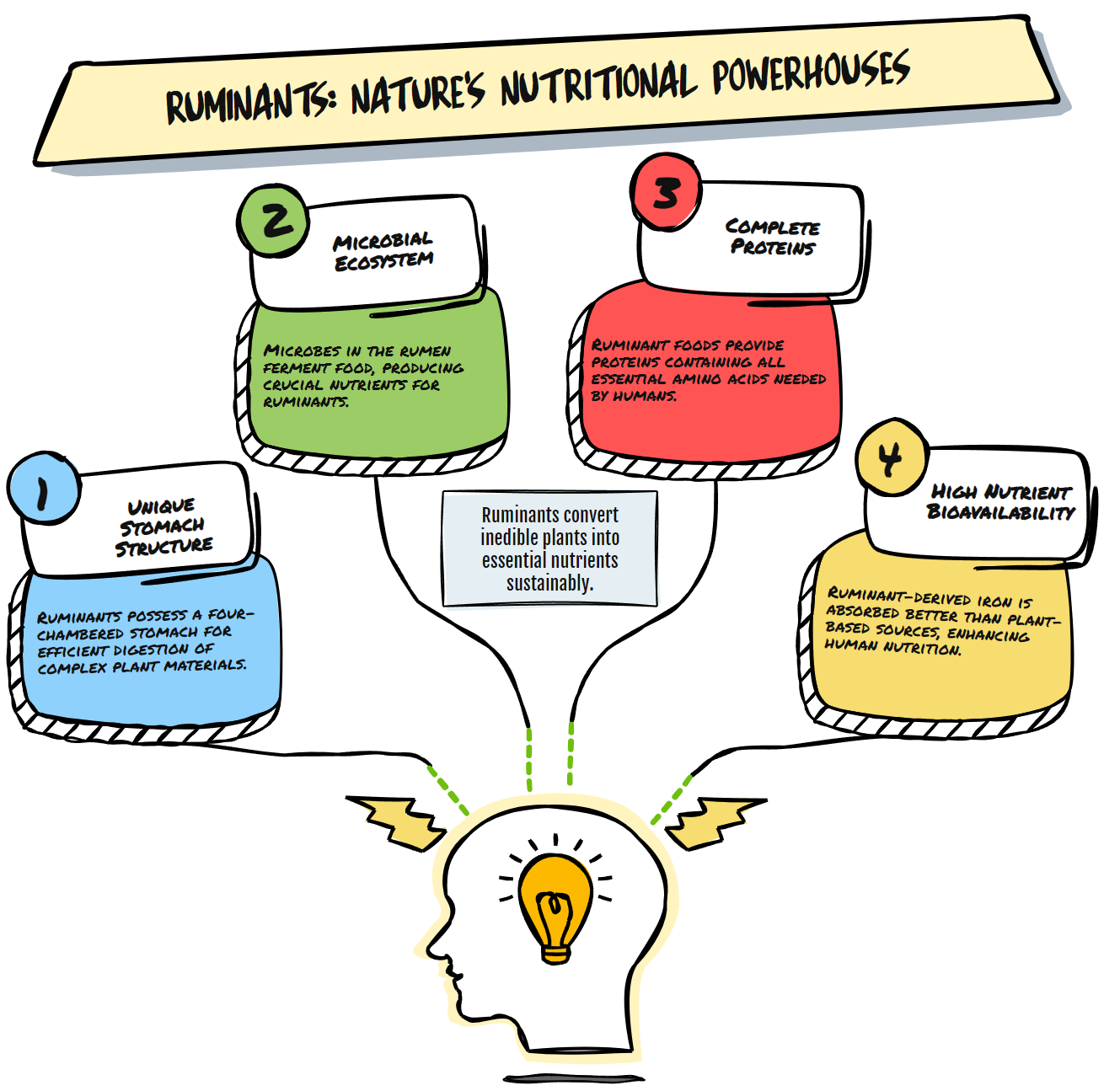

Ruminant animals have four stomachs, billions of microbes, and a biological superpower that shapes our food system. In nature's design, they stand apart as remarkable converters of the inedible into the essential.

Most people never consider the biological marvel inside cattle, sheep, goats, and bison. Yet this process fundamentally changes what humans can eat and how we interact with our environment.

The secret lies in a specialized digestive system that humans lack entirely.

Nature's Perfect Conversion Machine

Ruminants possess a unique four-chambered stomach that allows them to digest plant materials humans cannot process. The largest chamber, the rumen, holds up to 40 gallons in a mature cow and represents approximately 84% of the total stomach volume.

This isn't just bigger. It's fundamentally different.

Inside this chamber, an entire ecosystem of microorganisms breaks down cellulose and other complex carbohydrates found in grasses, hay, and plant matter. These microbes ferment these materials, producing essential nutrients that the animal absorbs.

Ruminants are genuine ecological powerhouses that transform inedible forage into high-quality protein, giving them a unique advantage in our food chain. This biological alchemy happens without competing with human food sources.

The implications are profound when we consider global food systems.

Nutritional Density Without Compromise

The nutritional profile of ruminant-derived foods reveals why they've been central to human diets throughout history.

Ruminant animals provide foods containing complete proteins with all essential amino acids, highly bioavailable heme iron, and vitamin B12, which is only found naturally in animal products. These nutrients are often lacking or less absorbable in plant-based alternatives.

Consider vitamin B12. Rumen microbes synthesize this essential nutrient using cobalt from the animal's diet. Humans cannot produce vitamin B12 themselves, making ruminant meat and dairy critical sources for this nutrient that supports neurological function and DNA synthesis.

Protein quality deserves special attention. Ruminant proteins contain all nine essential amino acids in proportions that closely match human requirements, making them some of the most efficient protein sources available.

Bioavailability matters as much as content.

The iron in ruminant meat is heme iron, which the human body absorbs at rates 2-3 times higher than non-heme iron from plant sources. This difference can be decisive for health outcomes for vulnerable populations prone to anemia.

Beyond Nutrition: Ecological Partners

The relationship between ruminants and ecosystems reveals another dimension of their value.

Properly managed grazing systems can benefit the environment. Research shows that well-managed ruminant grazing can sequester more carbon dioxide equivalents in the soil than are emitted by the animals, improving soil carbon, rainfall infiltration, and fertility.

Carbon sequestration occurs through a simple but elegant process. When ruminants graze, they stimulate plant growth to increase root development. These deeper, more extensive root systems effectively pump carbon into the soil.

The animals also distribute fertility across landscapes through their manure and urine, creating nutrient cycles that benefit the ecosystem.

Regenerative grazing practices mimic natural grazing patterns of wild herbivores, promoting diverse plant growth with deeper root systems that enhance carbon sequestration and soil health. The trampling effect of hooves helps incorporate plant matter into the soil, accelerating decomposition and nutrient cycling.

This creates a virtuous cycle where soil health improves, water retention increases, and biodiversity flourishes.

The Misunderstood Methane Question

Concerns about methane emissions from ruminants deserve honest examination. Ruminants do produce methane as a byproduct of their fermentation process. However, this must be understood in the proper context.

Unlike carbon dioxide from fossil fuels, which represents new carbon entering the atmosphere, biogenic methane from ruminants participates in a relatively short-term carbon cycle. The carbon in methane comes from plants that recently captured it from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

Methane breaks down in approximately 12 years, returning to the carbon cycle. When cattle populations remain stable, they create a steady state where methane emissions are balanced by methane breakdown.

This doesn't mean methane has no impact, but it does mean its climate effects differ fundamentally from those of fossil fuel emissions.

Rethinking Our Food Relationships

The ruminant's role in human nutrition reveals a more complex and beneficial relationship than often portrayed. These animals don't simply consume resources. They transform resources humans cannot use into highly nutritious foods while potentially benefiting ecosystems.

This transformation represents a form of biological cooperation that has evolved over millennia. Humans provide protection and management, while ruminants provide essential nutrition and ecological services.

The future of food systems will require a nuanced understanding of these relationships rather than simplistic categorizations of foods as "good" or "bad."

Properly managed ruminant agriculture represents one of the most efficient ways to produce complete nutrition while potentially regenerating landscapes. It allows humans to derive nutrition from marginal lands unsuitable for crop production.

When managed regeneratively, ruminants can help restore degraded grasslands, improve water cycles, and increase biodiversity. Their hooves break hard soil crusts, their manure feeds soil life, and their grazing stimulates plant growth when properly timed.

The Path Forward

Understanding ruminants as nutritional partners rather than competitors offers a more complete picture of sustainable food systems. The focus shifts from elimination to optimization.

The question becomes not whether ruminants should be part of our food system, but how to manage them for maximum benefit and minimum impact.

This means supporting grazing methods that mimic natural patterns, prioritizing soil health, and recognizing the nutritional density these animals provide. It means valuing quality over quantity in animal products.

The ruminant's ability to convert inedible plants into complete nutrition represents a biological gift. Our task is to honor this gift through management that respects both the animals and the ecosystems they inhabit.

When we do, we discover that these remarkable creatures offer sustenance and a path toward more regenerative relationships with our food and planet.