Rethinking Ruminants in the Climate Crisis

Rethinking Ruminants in the Climate Crisis

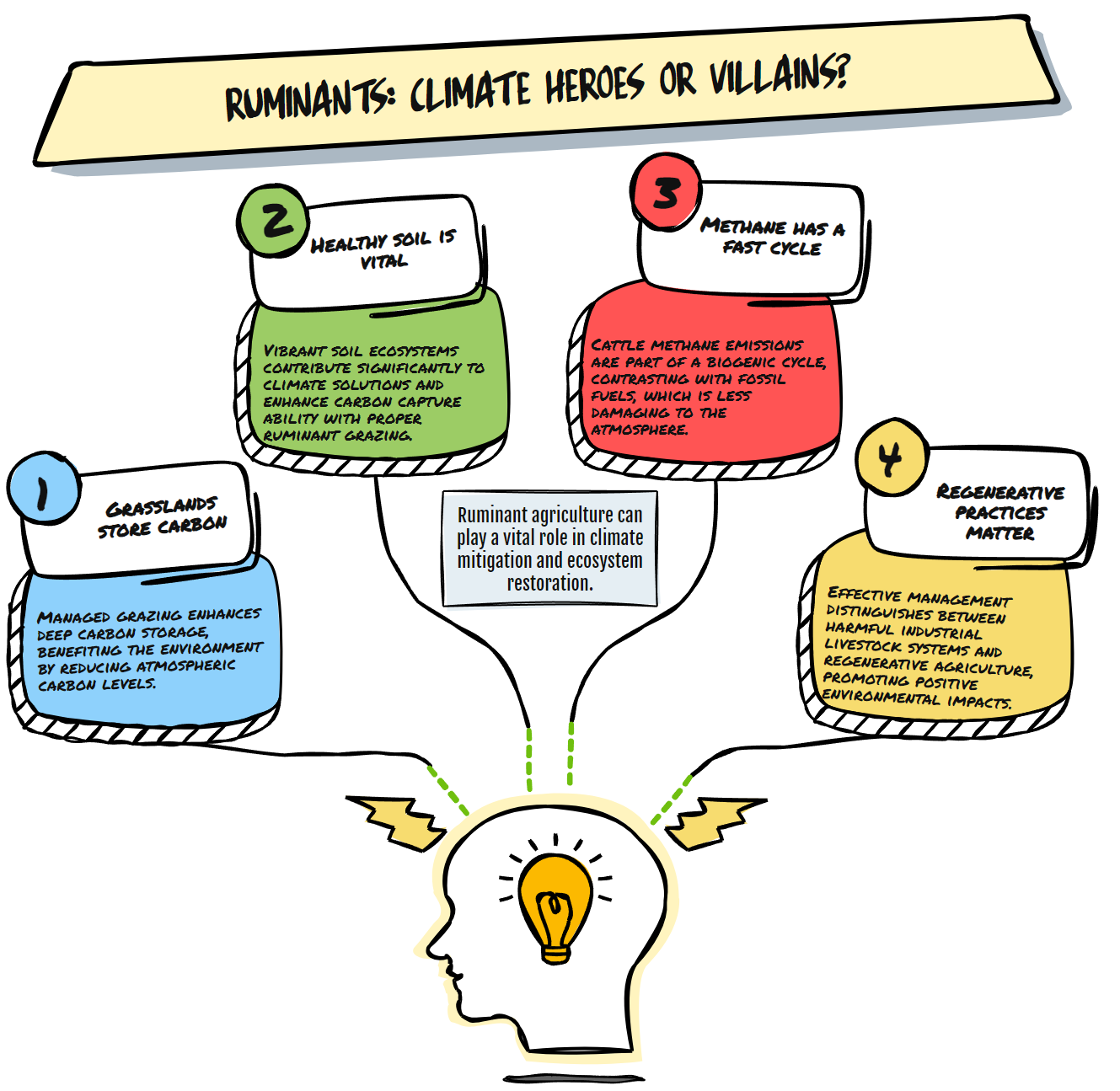

Cows are constantly blamed for everything from methane emissions to deforestation to water pollution. The narrative feels settled: reduce livestock, save the planet. But what if our understanding has been fundamentally incomplete? What if properly managed ruminant agriculture represents not an environmental liability but one of our most powerful tools for reversing climate change?

This isn't about defending industrial feedlots or clearing rainforests for cattle. Those practices deserve criticism. This is about recognizing that the relationship between ruminants and our planet is far more complex and potentially beneficial than most climate conversations acknowledge.

The Carbon Underground

When we discuss carbon sequestration, we typically think of trees. Yet, grasslands, when managed adequately with grazing animals, can store massive amounts of carbon underground and remain stable even during fires and droughts—the secret lies in how ruminants interact with these ecosystems.

Grasslands and grazing animals co-evolved over millions of years. These landscapes developed under the influence of herds that bunched together (avoiding predators), intensively grazed an area, and then moved on. This pattern stimulated plant growth, distributed seeds, broke soil crusts with their hooves, and fertilized the land with their waste.

Modern rotational grazing mimics these natural patterns. When appropriately managed, cattle can trigger grasses to push carbon deep into the soil through their extensive root systems. The grazed but not destroyed plants respond by sloughing off old roots and growing new ones, building soil organic matter.

Soil as a Living Climate Solution

Healthy soil isn't just dirt. It's a complex ecosystem teeming with microorganisms, fungi, and other life forms. When ruminants graze appropriately, they stimulate this underground ecosystem, enhancing its ability to capture and store carbon.

Consider the numbers: Some studies suggest that properly managed grazing lands can sequester between 1 and 8 tons of carbon per acre annually. Multiply that across the world's 3.5 billion acres of grazing land, and the potential becomes staggering.

Unlike technological climate solutions that require massive investment and infrastructure, regenerative grazing requires minimal external inputs. It works with natural processes rather than against them.

Beyond Carbon

The benefits extend beyond carbon sequestration. Well-managed grazing lands improve water infiltration, reducing both drought and flood risks. They increase biodiversity, providing habitat for countless species. They can also produce nutritious food from land unsuitable for crop production.

Approximately two-thirds of agricultural land globally consists of grasslands that cannot support crop production without significant irrigation or inputs. Ruminants convert inedible (to humans) cellulose into high-quality protein and other nutrients, effectively expanding the planet's food production capacity.

Addressing the Methane Question

Critics rightfully point to methane emissions from cattle as a climate concern. This potent greenhouse gas deserves serious attention. However, several factors complicate this picture.

First, methane from cattle is part of a biogenic carbon cycle, unlike fossil methane, which introduces new carbon into the atmosphere. The carbon in biogenic methane comes from plants that recently removed it from the atmosphere.

Second, methane has a relatively short atmospheric life of about 12 years, compared to carbon dioxide's centuries-long persistence. This means that stable herds (not increasing in size) reach a point where methane decay equals new emissions.

Third, certain grazing practices and feed additives can significantly reduce methane production in cattle.

The Industrial Context

Much of the legitimate criticism of livestock focuses on industrial production systems that bear little resemblance to the regenerative practices described here. Concentrated animal feeding operations, monocrop feed production, and associated deforestation deserve scrutiny and reform.

The distinction matters. Lumping all ruminant agriculture together misses crucial differences in environmental impact. Context, management, and integration with local ecosystems determine whether livestock harm or heal.

Nuance in a Polarized Conversation

Climate discussions often lack nuance. We seek simple villains and heroes. But agricultural systems resist such simplification. Their environmental impact depends on specific practices, regional contexts, and management decisions.

This complexity frustrates those seeking straightforward solutions. Yet embracing this complexity might unlock more effective approaches to our climate challenges.

The path forward requires moving beyond ideological positions toward evidence-based practices. It means distinguishing between destructive and regenerative agricultural systems rather than demonizing entire food production categories.

Reimagining Our Relationship with the Land

Perhaps the most profound shift involves reimagining our relationship with food systems. Rather than viewing agriculture as extractive, we can see it as regenerative. Rather than separating humans from nature, we can recognize our role within ecological systems.

Properly managed ruminants can help restore degraded landscapes, rebuild soil health, support biodiversity, and produce nutritious food while sequestering carbon. This potential deserves serious consideration in climate conversations.

The question isn't whether all ruminant agriculture is good or bad for the climate. The question is how we can transition toward systems that harness these animals' regenerative potential while minimizing their negative impacts.

The next time you hear blanket statements about cattle and climate change, remember that the story contains more promise and complexity than most headlines suggest. Our climate future may depend not on eliminating ruminants, but on reintegrating them properly into our landscapes and food systems.