How Meat Shaped Human Evolution and Rewired Our Brains

How Meat Shaped Human Evolution and Rewired Our Brains

Humans stand alone among primates. Our massive brains, complex societies, and technological innovations separate us from our evolutionary cousins. But what fueled this remarkable divergence? The answer might be simmering in your kitchen.

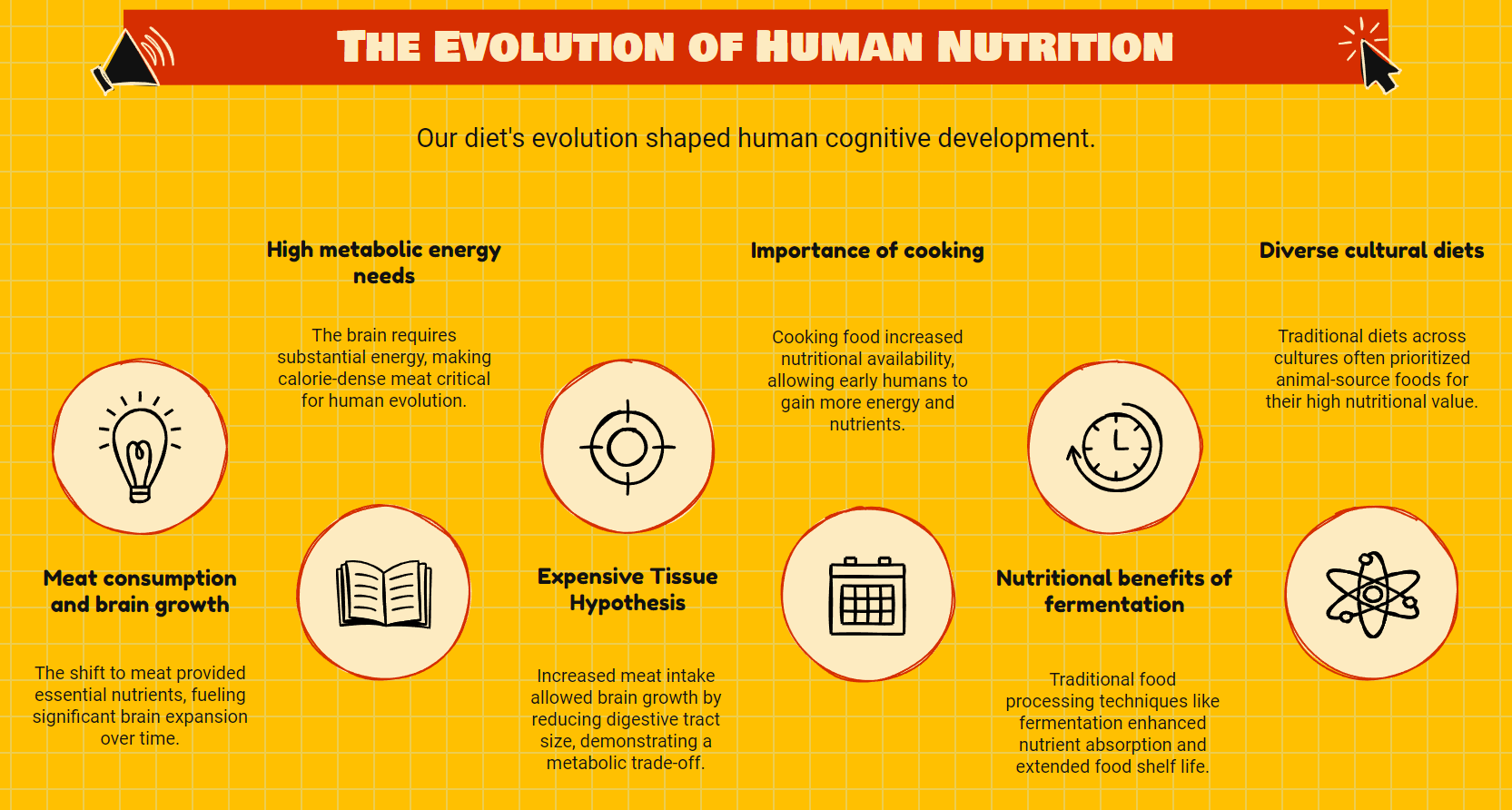

Anthropologists and nutritional scientists have investigated the critical relationship between human dietary patterns and our cognitive development for decades. The evidence points toward a fascinating conclusion: our ancestors' shift to meat consumption may have catalyzed the explosive growth of the human brain.

The Protein That Built Our Thinking

Roughly two million years ago, our early ancestors made a pivotal transition as climate change transformed lush forests into open savannas, and early hominids adapted by incorporating more animal products into their previously plant-based diets. This dietary shift coincided with a remarkable acceleration in brain growth.

The correlation is not coincidental. Animal proteins deliver a concentrated package of essential nutrients that plant foods cannot match in density or bioavailability. These include complete amino acid profiles, omega-3 fatty acids (particularly DHA), vitamin B12, zinc, and heme iron. Each plays a crucial role in neural development and cognitive function.

Consider the brain's extraordinary energy demands. Despite accounting for merely 2% of body weight, our brains consume approximately 20% of our resting metabolic energy. This metabolic expense required a rich, calorically dense fuel source that meat uniquely provided.

Leslie Aiello and Peter Wheeler proposed the influential "Expensive Tissue Hypothesis" in the 1990s, suggesting that increased meat consumption allowed our digestive tracts to shrink while our brains expanded. The high-quality nutrition from animal foods permitted this metabolic trade-off, fundamentally altering our evolutionary trajectory.

Beyond Raw Consumption

The story grows more complex when considering how our ancestors processed their food. Archaeological evidence suggests that controlled use of fire for cooking dates back at least 400,000 years, with some controversial findings potentially pushing this timeline further.

Cooking revolutionized human nutrition. Heat profoundly transforms food, breaking down tough plant fibers, denaturing proteins, and neutralizing various anti-nutrients. These changes dramatically increased the bioavailability of calories and nutrients from both plant and animal foods.

Harvard anthropologist Richard Wrangham argues in his "cooking hypothesis" that thermal food processing was not merely beneficial but necessary for human evolution. Cooking effectively provided a form of "external digestion" that reduced the energy costs of breaking down food internally, further freeing metabolic resources for brain development.

Traditional food processing extends beyond cooking. Fermentation, drying, smoking, and other preservation techniques emerged across diverse human cultures. These methods extended food availability beyond seasonal constraints and enhanced nutritional profiles through bacterial pre-digestion and chemical transformations.

Cultural Variations With Common Threads

Examining traditional diets worldwide reveals fascinating diversity in food sourcing and preparation. Arctic Inuit populations thrived on diets consisting almost entirely of animal products. Tropical forest dwellers balanced hunting with gathering diverse plant foods. Agricultural societies developed complex systems around staple crops supplemented with animal products.

Despite this variation, anthropological research reveals a common thread: virtually all traditional cultures prioritized animal-source foods when available. From the organ-meat-first consumption patterns of hunter-gatherers to the careful preservation of dairy fats in pastoral societies, our ancestors recognized the nutritional value of these foods, even without understanding the biochemistry involved.

Traditional wisdom often anticipates modern nutritional science. Many cultures practiced nose-to-tail eating, consuming organs and other tissues that now contain concentrated micronutrients. Others developed complementary plant-animal food combinations that enhanced nutrient absorption, such as pairing iron-rich meats with vitamin C-rich vegetables.

Modern Implications of Ancient Patterns

Our evolutionary dietary history offers valuable context for contemporary nutrition debates. The human digestive system and metabolic pathways evolved in environments where specific food processing techniques and combinations were universal. This biological reality suggests wholesale departures from these patterns may have unintended consequences.

Modern food processing differs fundamentally from traditional methods. Where traditional techniques generally preserved or enhanced nutritional value, many industrial processes prioritize shelf stability, palatability, and profit margins over nutritional integrity. The resulting ultra-processed foods bear little resemblance to anything in our evolutionary experience.

This perspective doesn't demand a rigid "paleo" approach. Human dietary adaptability remains one of our species' greatest strengths. However, it suggests optimal nutrition might incorporate elements from our evolutionary heritage while leveraging modern scientific understanding.

Balancing Ancient Wisdom With Modern Knowledge

The relationship between meat consumption, food processing, and human evolution offers nuanced insights rather than simplistic dietary prescriptions. Our species' success stems partly from our omnivorous flexibility and ability to extract nutrition from diverse food sources through cultural innovation.

Understanding this evolutionary context allows us to approach modern dietary questions more sophisticatedly. Rather than viewing nutrition through reductionist lenses focusing exclusively on isolated nutrients or ideological frameworks, we can appreciate the complex interplay between biology, ecology, and culture shaping human nutritional needs.

The story of human nutrition reveals a remarkable journey of adaptation. From the savanna-dwelling hominids who first incorporated more animal products into their diets to the diverse cultures that developed sophisticated food processing techniques, our nutritional history reflects continuous innovation guided by the fundamental requirements of our uniquely energy-hungry brains.

This evolutionary perspective reminds us that nutrition science remains a developing field. We continue to discover new dimensions of how foods interact with our biology, suggesting that ancient wisdom and cutting-edge research have valuable roles in shaping our understanding of optimal human nutrition.